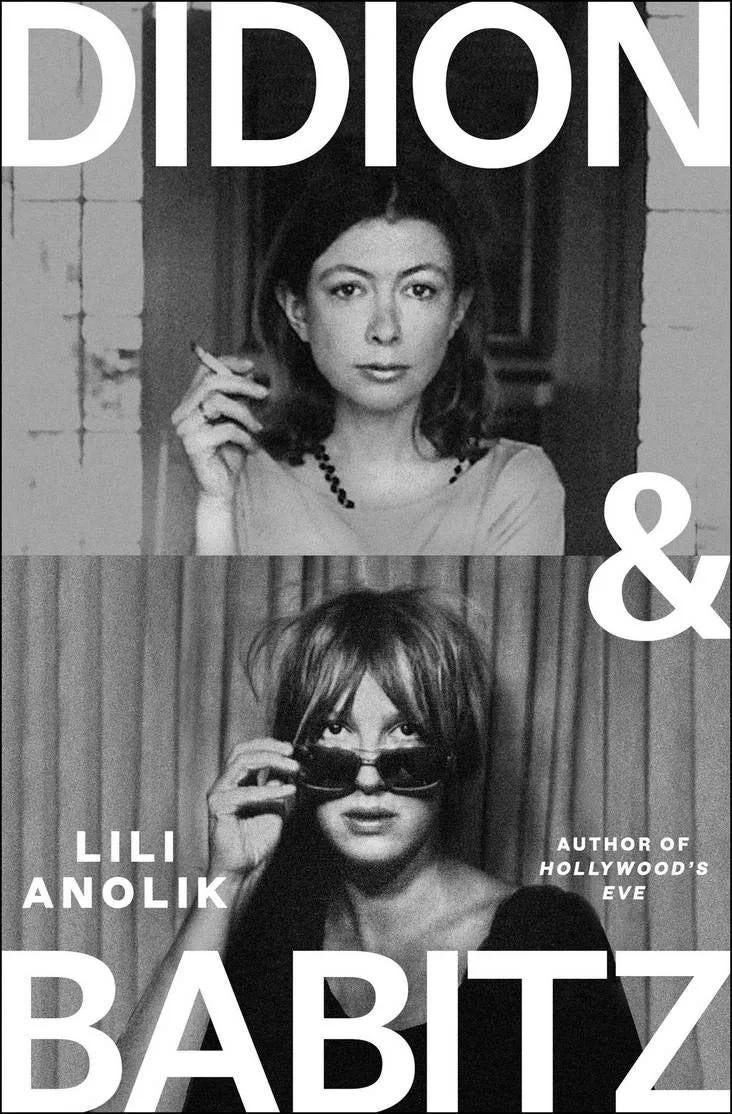

LA Women

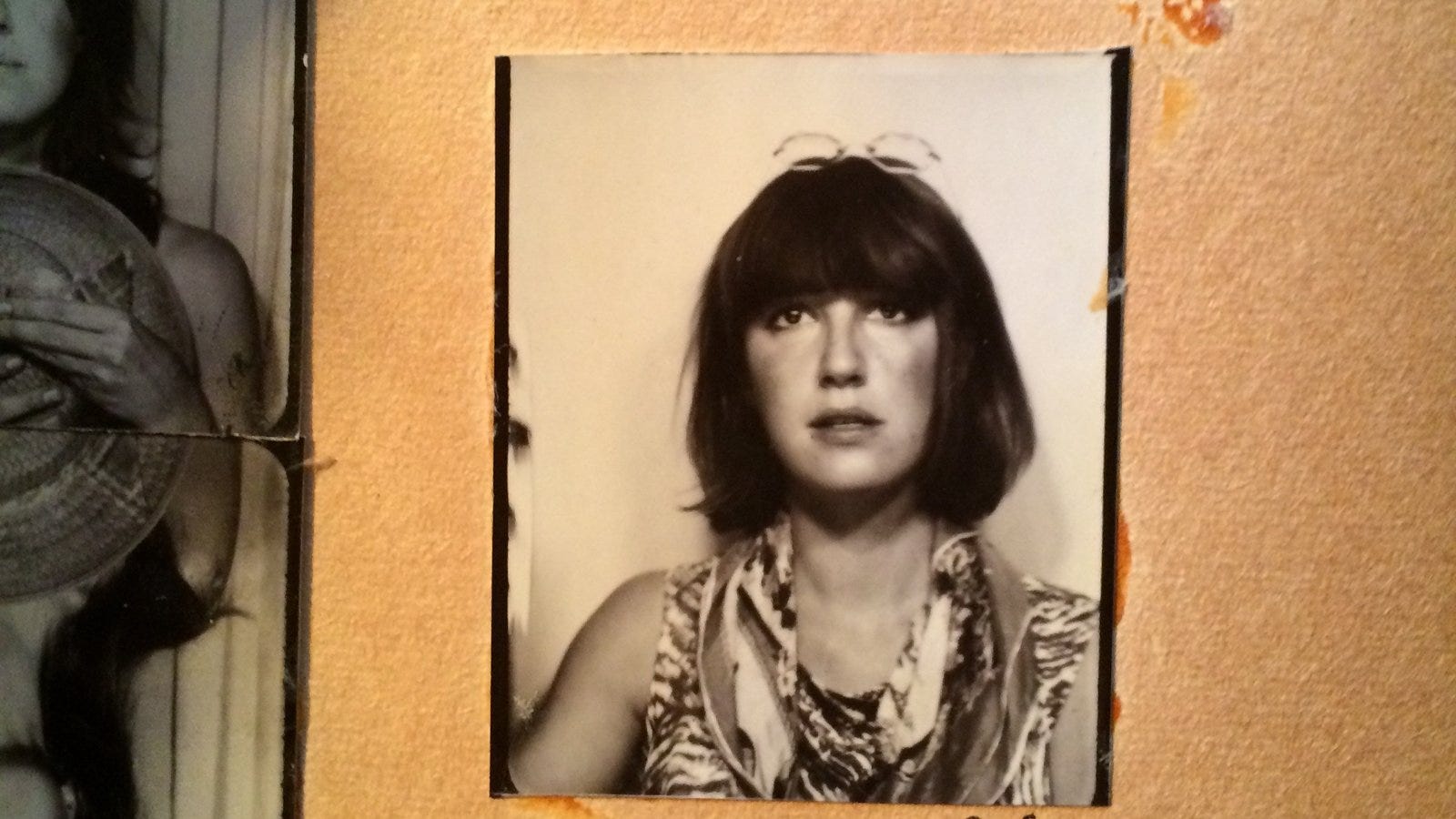

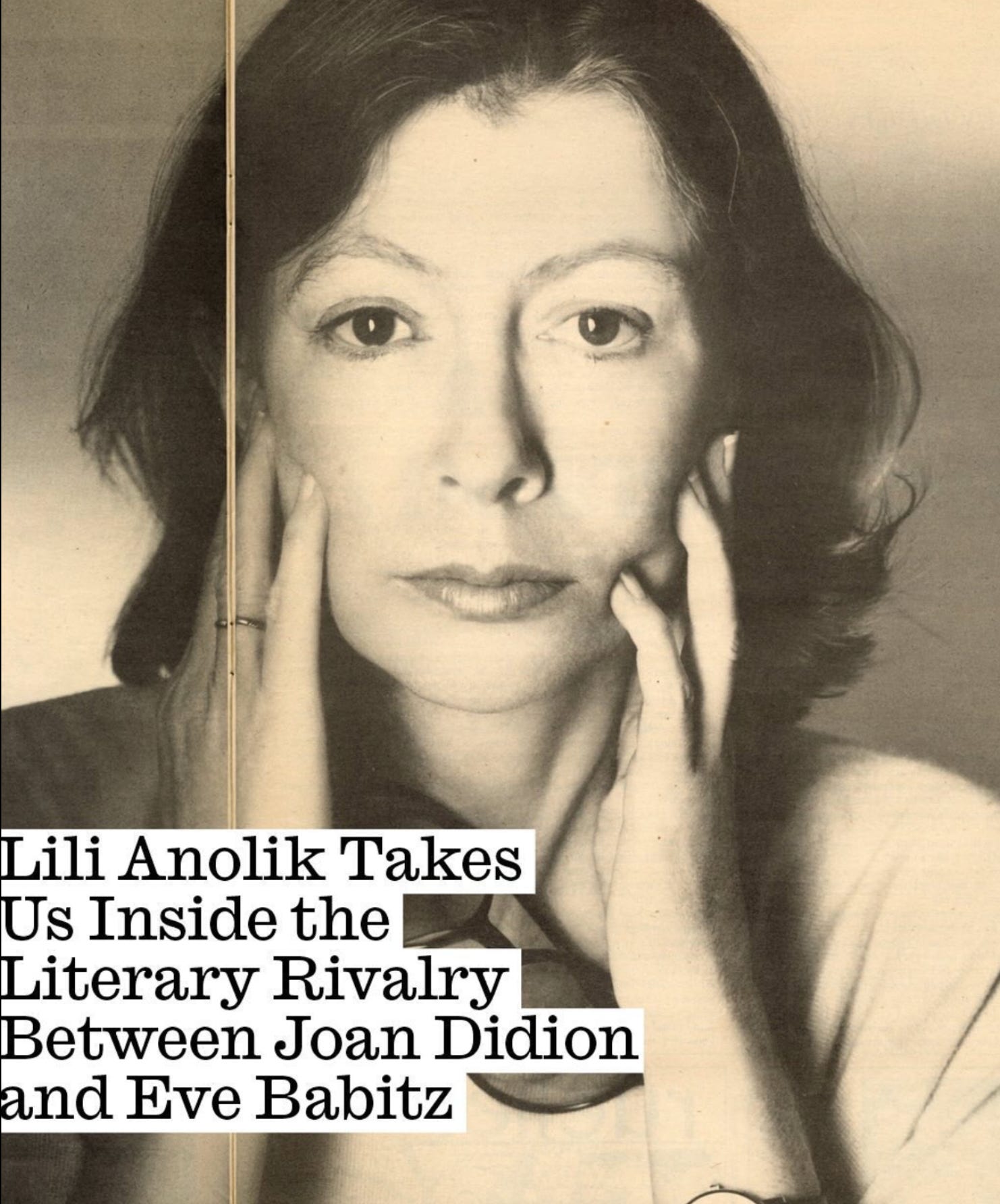

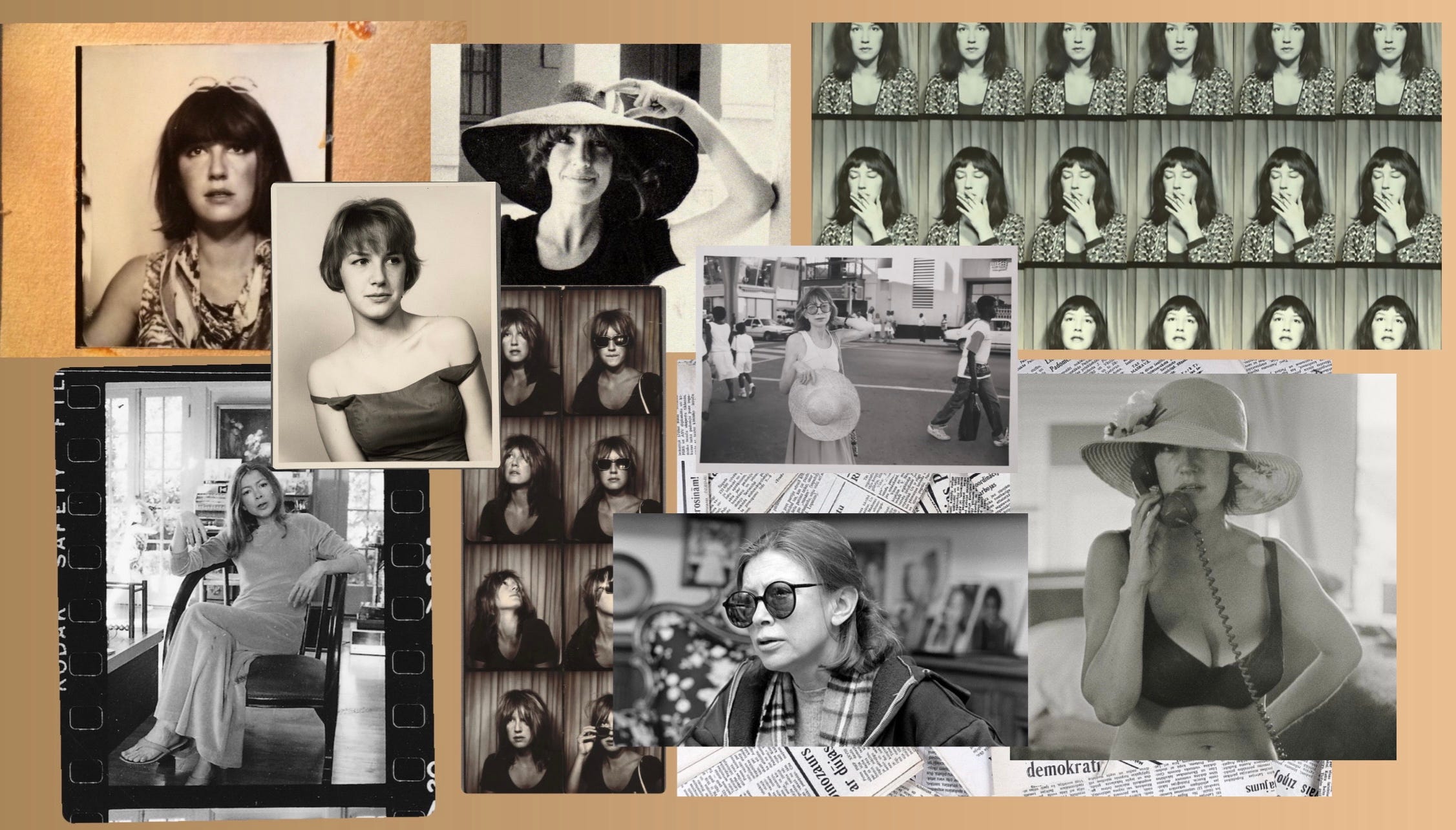

Lili Anolik on the Fascinating Dynamic Between Literary Friends and Rivals Joan Didion and Eve Babitz

“I did not become famous but I got near enough to smell the stench of success. It smelt like burnt cloth and rancid gardenias, and I realized that the truly awful thing about success is that it's held up all those years as the thing that would make everything all right. And the only thing that makes things even slightly bearable is a friend who knows what you're talking about.”

―Eve Babitz,Slow Days, Fast Company: The World, the Flesh, and L.A.

Who is Lili Anolik?

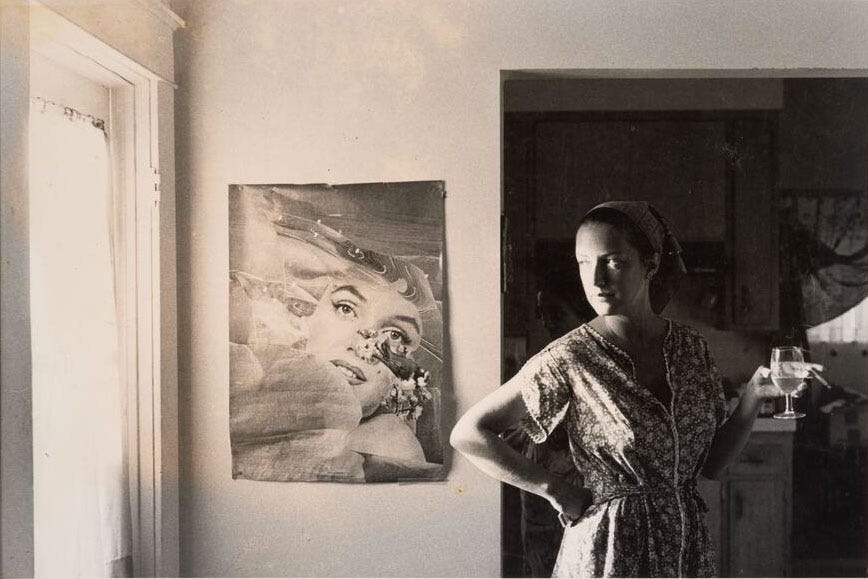

Mother of two, a contributing editor at Vanity Fair, and a writer at large for Air Mail, known for exploring the contradictions, ambition, and sheer force of personality that shape cultural icons. In Hollywood’s Eve, she reintroduced the world to Eve Babitz, the sharp-witted, hedonistic chronicler of Los Angeles, whose work had long been overshadowed by her legendary status. Now, in her latest book, she turns her attention to the complicated dynamic between Babitz and Joan Didion, the queen of cool, whose tightly controlled prose and persona made her one of the most enduring literary voices of the 20th century.

Though both women inhabited the same world, Babitz and Didion saw it through radically different lenses—one immersive and indulgent, the other detached and surgical. While Didion deconstructed the mythology of California, Babitz lived inside it. I had the privilege of listening to the audiobook alongside a friend and fellow writer during office renovations, breaking down each chapter in real-time and comparing notes on the evolving dynamics between these two literary forces. After finishing the book, I was delighted to connect with Lilii about it. In this conversation, she delves into the tensions between Babitz and Didion, their influence on each other, and what their work reveals about how women write, mythologize, and navigate a world that often reduces them to symbols rather than voices.

About the Book:

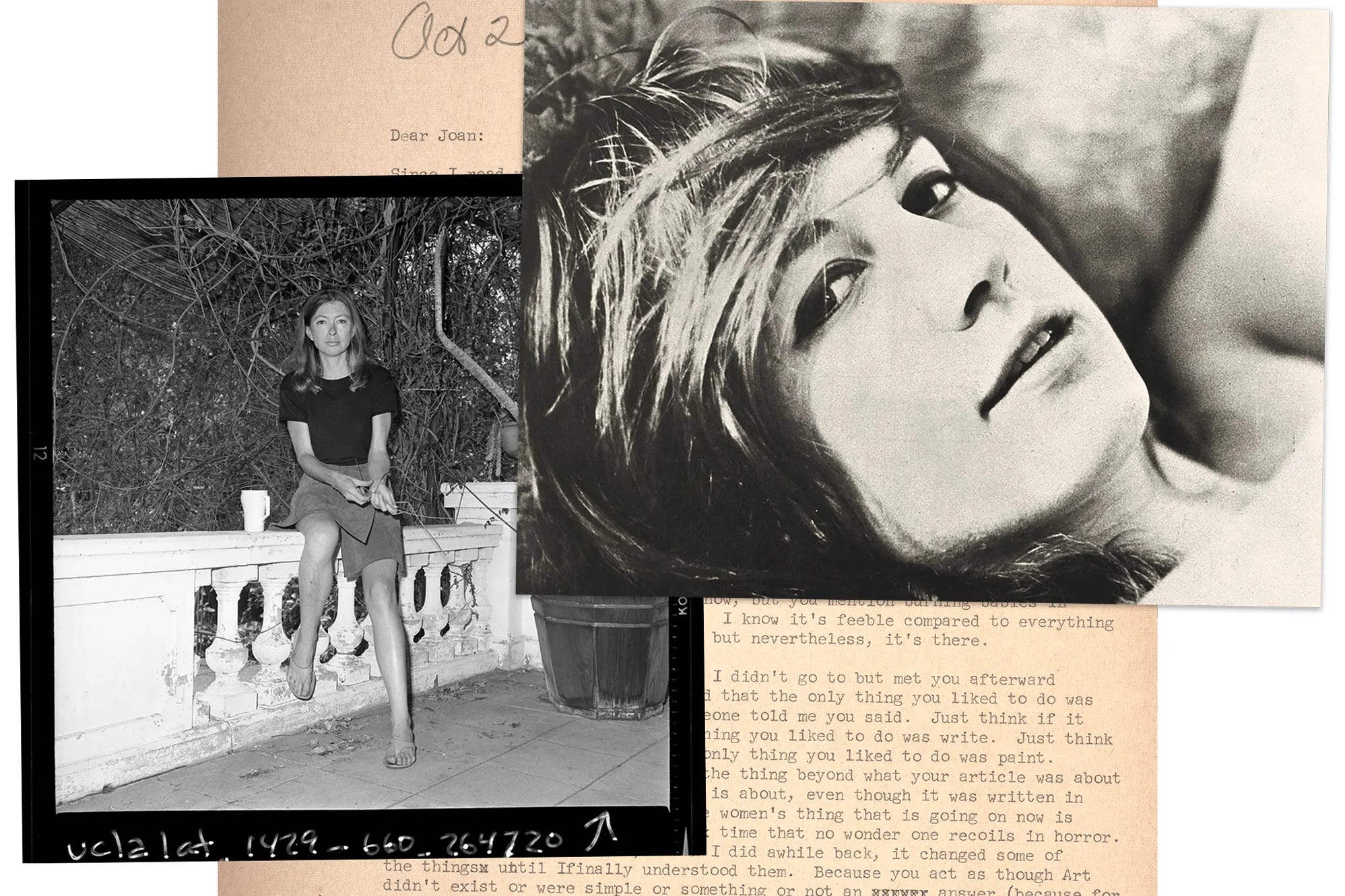

“Eve Babitz died on December 17, 2021. Found in the wrack, ruin, and filth of her apartment, a stack of boxes packed by her mother decades before. The boxes were pristine, the seals of duct tape unbroken. Inside, a lost world. This world turned for a certain number of years in the late sixties and early seventies and centered on a two-story rental in a down-at-heel section of Hollywood.

7406 Franklin Avenue, a combination salon-hotbed-living end where writers and artists mixed with movie stars, rock ‘n’ rollers, and drug trash. 7406 Franklin Avenue was the making of one great American writer: Joan Didion, a mystery behind her dark glasses and cool expression; an enigma inside her storied marriage to John Gregory Dunne, their union as tortured as it was enduring. 7406 Franklin Avenue was the breaking and then the remaking—and thus the true making—of another great American writer: Eve Babitz, goddaughter of Igor Stravinsky, nude of Marcel Duchamp, consort of Jim Morrison (among many, many others), a woman who burned so hot she finally almost burned herself alive. Didion and Babitz formed a complicated alliance, a friendship that went bad, amity turning to enmity.

Didion, in spite of her confessional style, is so little known or understood. She’s remained opaque, elusive. Until now.

With deftness and skill, journalist Lili Anolik uses Babitz, Babitz’s brilliance of observation, Babitz’s incisive intelligence, and, most of all, Babitz’s diary-like letters—letters found in those sealed boxes, letters so intimate you don’t read them so much as breathe them—as the key to unlocking Didion. And “what the book makes clear is that Didion and Babitz were more alike than either would have liked to admit” (Time).”

Eve Live on C-SPAN

Calling Joan "the only sensible person in the whole world in those days."

Q. Can you give us a little background? Where do you live, and what first inspired you to start writing? Do you have a strict process while working on a book?

People often assume that I live in L.A. A reasonable assumption since I write almost exclusively about L.A. and L.A.-ish subjects. But, as it happens, I live in New York—the city Eve Babitz couldn’t get out of fast enough—with my guy and our two sons.

I was a terrible sleeper as a kid. (I’m still a terrible sleeper. I can’t keep my eyes shut—too wired.) The agreement I came to with my parents was that, if I stayed in bed, I could leave the light on as long as I wanted. So, before I was a writer, I was a reader. My dad had all these old Pauline Kael collections lying around. (Kael was a movie critic in the sixties, seventies, and eighties, though that’s a depressingly reductive description of her.) She was a huge influence early on. The way she thought and wrote just thrilled me. She made it seem as if writing was the highest calling, the absolute best, most worthwhile thing you could do with your curiosity, your energy, your enterprise.

Okay, well, it’s not that my writing process is strict so much as that my writing rituals are weird. My favorite time to write is post-midnight, pre-dawn—when no one normal is awake, basically, just vampires and nightcrawler-types. I have to sit at my desk a set number of hours, even if most of those hours are spent staring into space. I have to use a Cambridge yellow legal pad and a PaperMate black felt tip pen. I have to drink Coca-Cola (in a bottle, never a can). Oh, and I absolutely have to listen to the same song on repeat for the whole day.

Aren’t you sorry you asked the question, Jessica? Who would want to know this shit?!?

Q. As a writer, what drives your interest in exploring the lives and work of other writers?

What drives me is obsession. And I don’t know how exactly to trace the steps of obsession. (That you don’t understand your obsession is, I think, part of what makes it an obsession. Obsession is, above all, irrational.)

Joan and Eve are for sure an obsession. So is Bret Easton Ellis. (I did a podcast on the writers of Bennington College, class of 1986—Bret Ellis, Donna Tartt, Jonathan Lethem—a few years ago.) But I also did something longform on the underage scandal of adult star Traci Lords. In that case, it was the mystery element that compelled me: Who turned in Traci to the Feds? Who dropped the dime? And the project I’m currently working on involves Courtney Love, not a writer. Or, at any rate, not a writer primarily. Though her grandmother, Paula Fox, was certainly a writer, and a very good one.

Q. What initially drew you to Eve Babitz as a subject?

In 2010, I came across this great quote on L.A. and sex. It was attributed to Eve Babitz. I’d never heard of such a person, and there was virtually nothing about her online. But I was able to track down one of her books (they were all out of print back then), and I couldn’t believe how good it was. Reading her, I felt this sense of deep, almost delirious delight. Her writing—its exuberance, its candor, its aphoristic wit and sly erudition—was so purely pleasurable. I felt this sense of discovery, too. I was sure, was absolutely convinced, that she was the secret genius of Los Angeles.

I began to stalk her. I could use a less aggressive phrase—pursued her? courted her?—but, really, it was straight-up stalking. I mean, I was relentless. I wrote her letters. She didn’t write back. I left her voicemails. She didn’t call back. It took two years to convince Graydon Carter to let me profile her for Vanity Fair. As soon as he agreed, I wrote and called some more. Still nothing. I befriended her sister, her cousin, several of her many—many, many—ex-boyfriends. (Desperate times, desperate measures, etc.) Eventually, she got either hungry or curious or both and told one of those ex-boyfriends that I could take her to lunch. I hopped a plane to L.A. the next morning.

Cut to a few years later. Not only were all Eve’s books back in print, but she’d become this sensation, this phenomenon—a bona fide thing. You had the actress Emma Roberts posting on Instagram a picture of herself on a chaise longue, Sex and Rage spread-eagled on her chest, the polish on her nails color-coordinated with the lettering on the book’s cover. You had model-mogul Kendall Jenner photographed on a yacht in a bikini, Black Swans sticking out of her tote bag. You even had Eve getting name-checked on the Gossip Girl reboot, for goodness’ sake. She went from nowhere to everywhere in the blink of an eye.

You want to know what all this felt like to me? Like my obsession was contagious, a communicable disease, and I’d somehow managed to infect the literary establishment. Which was a thrill, of course. (Isn’t that what every writer dreams of? His or her words having an actual effect on the world, changing things in a way that can be seen and felt?) I’d be lying, though, if I didn’t admit to the occasional pang of regret. As I said, I thought of Eve as L.A.’s secret genius. Only I’d blabbed and now the secret was out. No longer was she mine all mine.

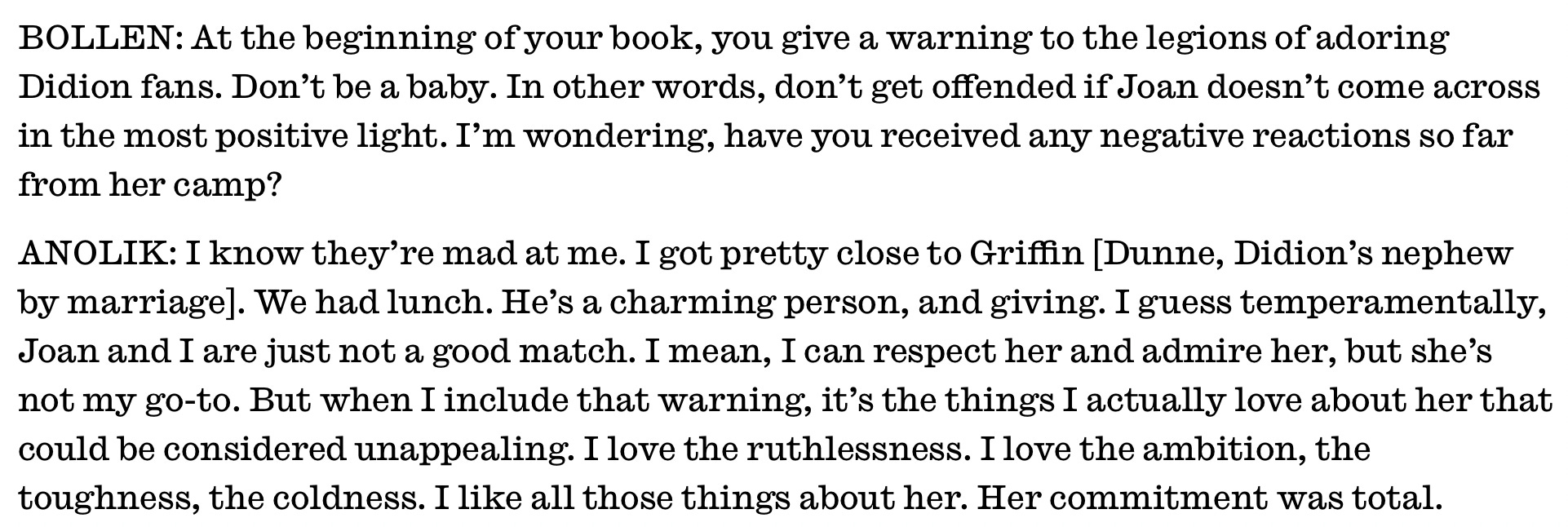

Q. You are transparent about the fact that you favor Babitz over Didion. Is that simply a classic writer's bias towards her own subject? A matter of your taste as a reader? A matter of your taste in characters? Your taste in general?

It sounds crude to say that Joan isn’t my type, but Joan isn’t my type. We’re just not a good match. I find her high-handed, high-nosed, self-serious. Her writing is sophisticated—she’s an undeniably great stylist, the most influential since Hemingway, I’d argue—but her ideas, at least her ideas about L.A., are not sophisticated. In her famous L.A. novel Play It as It Lays, she portrays the city as a twentieth-century Sodom and Gomorrah; a place that looks like heaven but feels like hell, populated by people who have beautiful faces and ugly souls. This thinking—thinking in quotation marks—isn’t just corny, it’s simple-minded. An adolescent’s idea of deep.

Eve, who emphatically is my type, takes the opposite attitude: one of amused, worldly skepticism. I love Slow Days, Fast Company—her best book—for its panoramic, kaleidoscopic view of L.A., for its utter lack of interest in passing judgment on its characters’ morals, for its anarchic pagan permissiveness. To me, Eve’s way of looking at the world is so much hipper, so much more tough-minded. So much more profound, as well.

And, okay, you’re right, Jessica. Early in the book, I do confess that I’m team Eve. Later on, though, I confess that that confession is phony! Look, Joan and Eve represent the two halves of American womanhood. They’re superego and id, Thanatos and Eros, yang and yin. To pick a side is dumb dumb dumb. As if both sides aren’t equally powerful, equally necessary. And it’s even dumber of me to pretend that a side is picked for good, as though I don’t sometimes drift from Eve’s side to Joan’s when I think no one is watching.

And, listen, I love Joan for her smarts, her steeliness, her fanatically high standards, the sheer force of her will. How can you not?

Q. In your book, you delve into how both Didion and Babitz perceived themselves through the eyes of others. Babitz is candid about her vanity, anxieties, and fleeting status as a "piece of ass," while Didion's self-presentation feels more opaque, requiring inference and projection. How do you interpret the role of artifice in their writing—and in the lives of women writers in general?

Joan and Eve were each other’s shadow selves in almost every way imaginable. Doubles who were, at the same time, total opposites. So, Joan vs. Eve is head vs. body, wife vs. mistress, observer vs. participant, craftsperson vs. improvisor, control vs. chaos.

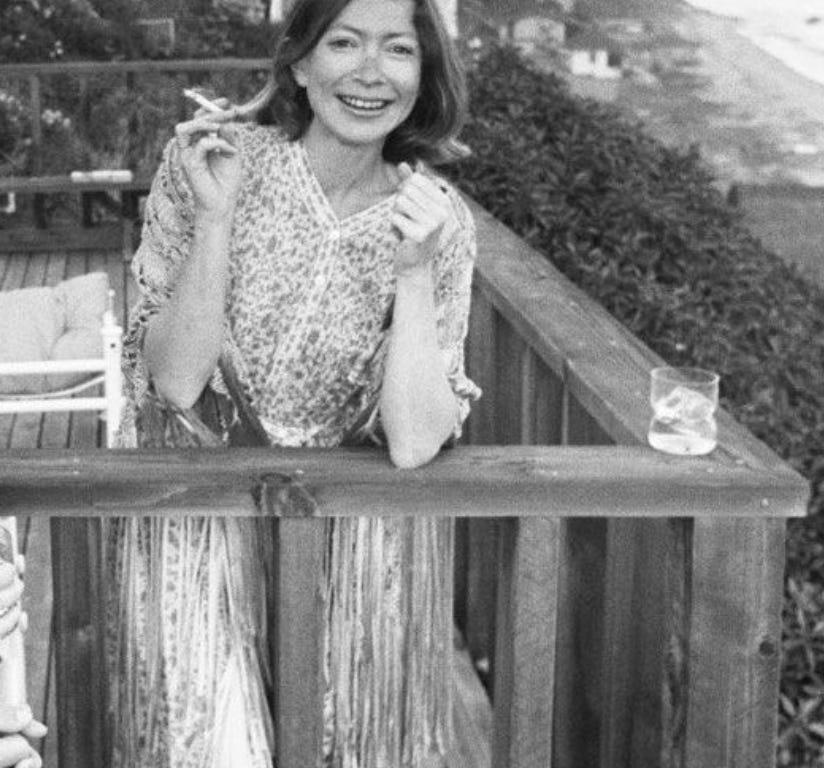

Joan was a brilliant writer. But she was every bit as brilliant a careerist. She was so shrewd about constructing a persona—silent, withholding, in the thick of it yet above the fray, cooler than cool—and I believe it beguiled as much as her books did.

Eve, on the other hand, aspired to amateurism. To be a careerist was, in her mind, antithetical to being an artist. (The worst thing she can think to accuse Joan of is “a kind of serious professionalism.” Like, that’s her nastiest insult, the biggest thunderbolt she can hurl!)

I believe that Eve didn’t catch on in her day—when she was actually living her life, writing her books—because she was too much the embodied creature to create a persona. (Why would she give a shit about presenting as the thing? She was the thing.) With the Vanity Fair piece, I created a persona for her, pulling together her wild, helter-skelter life, shaping it into a narrative that cohered in a viable way: goddaughter of Igor Stravinsky, nude of Marcel Duchamp, fuck buddy of Jim Morrison, Harrison Ford, Steve Martin, Annie Leibovitz. Eve is now not just a literary heroine but a cultural heroine, same as Joan. What she stands for is pleasure, provocation, extremism, to-thine-on-self-be-true, a reckless good time. She is now, in other words, a persona—a brand, in 2025 parlance. And that brand is the un-Joan, the anti-Joan.

Q. Didion often wrote about her physical presence and was famously stylish. As a journalist, her self-presentation may have been a deliberate part of her craft. What led you to interpret these details—and Babitz's feelings about them—as possibly cynical?

It was really Eve who interpreted Joan’s details cynically. As Eve saw it, Joan emphasized, almost fetishized, her smallness, her frailty. And, oh, did that make Eve mad! (Eve thought that Joan, this formidable person—wildly ambitious and dauntingly achieving—was passing herself off as a wispy little wouldn’t-hurt-a-fly wallflower in order to get in good with men. Eve was calling Joan a sycophant, basically. A suck-up)

So, for Vanity Fair’s September 2022 issue, I did a piece on a letter—a tirade in the guise of a letter, I should say—that Eve wrote to Joan in 1972. In it, she asked, “Could you write what you write if you weren’t so tiny, Joan?” I posted the piece on social media. All of a sudden, Courtney Love began flooding me with DMs about the poison pen letters she and Madonna used to exchange. She went on about how she had other tiny friends, but that Madonna’s tininess, for whatever reason, pissed her off. That’s the moment I realized that Joan and Eve was bigger than Joan and Eve, that the conflict between them wasn’t just personal, was universal.

So, in the Madonna/Courtney scenario, Madonna is, obviously, the Joan stand-in: trim, disciplined, eye on the prize. And Courtney is the Eve: out of control maybe but also busting loose, free of the shackles that bind the spirit. And there was an intense mutual attraction/intense mutual repulsion between Madonna and Courtney, same as there was between Joan and Eve. And the moment I understood this is the moment I understood that if I do my job right with this book, all women readers will be asking themselves, “Am I a Joan or an Eve?” Because you’re either one or the other. That’s just how it is.

Q. Your uncovering Joan's secret love, Noel Parmentel, was one of the most stunning discoveries in the book. As a long time fan of Joan, I was shocked to learn about it. What was it like first finding that letter and later meeting him in person?

I was aware that Noel Parmentel existed. (He has an almost mythical status in the Didion world.) And of course I tried to get in touch with him—wrote him letters, wrote him through Facebook. But I didn’t hear back. I knew he was in his late nineties, so I figured that he was in no shape for an interview and that I ought to leave him alone. (See? I have some sense of decency.)

But then I met the L.A. writer Stephanie Danler for lunch. I was already almost done with a first draft of the book. I was telling Stephanie about it, and she asked if I’d spoken to Noel yet. I told her that I wasn’t pursuing him anymore, that I was letting him go—yakkety-yakked about not hassling the elderly. She cut me off. I couldn’t do a book about Joan without talking to Noel, she said. I went back to my hotel room and picked up the phone. I called Noel’s landline and—surprise, surprise—he answered. A few days later, I was at the house he shared with his long-time partner, Vivian Sorvall, in Connecticut. And we spoke regularly for the next six or so months.

Noel really broke Joan open for me. She’s an opaque character, you know? On the surface, she’s a confessional writer, and very open. If you look closer, though, you see that she’s actually quite guarded, quite hidden. She only tells you what she wants you to know. So, hearing what Noel had to say was revelatory. I was shocked—really, truly floored—to learn that he was the great love of her life, not John Gregory Dunne. She met him when she moved to New York in the late fifties. He was a journalist, a Southerner, a compulsive drinker and womanizer, a rascal, a cad, a man of the world, a charmer and a smoothie—a character straight out of a Hemingway novel. Noel was Joan’s first lover, Joan’s first promotor. He made it happen for her professionally, got her pieces into magazines and got her first novel, which had been rejected by over a dozen houses, into print. When he made her understand that he would neither marry her nor give her a baby, she had a nervous breakdown. (The one she wrote about so famously in “Goodbye to All That.”) So he found her a husband. Dunne was an acolyte of his, a sort of little-buddy sidekick type. Noel told Joan to marry Dunne and she did. Marrying Dunne was, I believe, her way of marrying Noel.

Noel completely rocked my understanding of Joan, of Joan’s marriage, of Joan’s emotional, psychological and sexual life, and I came this close to missing him! It’s scary to think. I mean, at a certain point you have to turn your research into narrative—into history, basically—but new data is constantly being introduced. The past is never not changing.

Q. Women often face unique pressures in how they critique themselves and one another. I think of something I've heard older women describe as the "lifeboat theory": there is only so much room in here, and we can't all fit, so some of us must be pushed back into the surf. Do you think rivalries such as the one you believe existed between Didion and Babitz are becoming an antiquated concept?

No, no, I think that the dynamic between Joan and Eve is fundamental to human nature and will never die out. I call what they had a “friendship,” but “friendship” is an inadequate word, is too flimsy, puny, is flat-out not up to the job of describing the heavy, underwater thing that was going on between them. What they had was at once more than a friendship and less; was a mixture of true love and true hate; was chemical, was primal. And I’d bet that almost every woman on the planet has experienced some version of it.

In my mind, I was writing the Elena Ferrante series My Brilliant Friend, only set in L.A. and non-fiction.

Q. Your book seems perfect for adaptation into a series. Have you considered this or had any discussions about it?

A lot of discussion, but no decisive action. Not that I can talk about, anyway. But yeah, I agree, the book is a natural for adaptation. I’d imagine any number of actresses would jump to play Joan or Eve. If you look good in sunglasses, go for the Joan role, I guess. If cleavage is your thing, go for the Eve.

To start the New Year right, I’m thrilled to share an exclusive offer: 20% off for life on Pique’s Daily Radiance Vitamin C. Take this opportunity to transform your health and skin radiance in 2025 - your glow-up starts here! Click for 20% Off for life

Wow! Love this essay and the story of these two women. I’m a longtime fan of Didion. She was my inspiration for my journalism major at undergraduate. I know less about Babitz but look forward to reading this book about their connection!

Are you Joan or Eve?

So very interesting!

She neglects to use the word Archetypes; each of these women were embodying various archetypes. Universal, timeless symbols of humanity, in this case of womanhood. What are.the tactics or strategy or guile one uses to surf through life with or like Eve who perhaps relied on instinct, intuition perhaps wild abandon, giving into the life of the.moment and enjoying it.

Gratefully, Eve has been resurrected,. in this case to be an equal or better of Joan.

It seems Eve loved the.moment of life and Joan used it as an analytical.tool in her work. Fascinating back story w Noel, who would Joan have been if she had captured her Tu es l'amour de ma vie.

Kudos,.to LilI!

Tre.Fascinant!