When the Jury Gets it Wrong

A growing trend of activists jurors is fueling new reasons for appeal

In a modern cyber era, we’ve seen technology and social media alter nearly every aspect of our lives. One of the more surprising consequences of growing tech has been the silent impact on our justice system, specifically with jurors.

This last year, we’ve witnessed several high-profile trials seeking (and winning) appeals based on the moral errors of jurors. We can count Maxwell, Weinstein, and now possibly Trevor Milton on that list.

The question now is: how long do we continue to ignore signs of an outdated juror process? All it takes is one compromised juror to sway a jury. What can the courts do to keep the integrity of the justice system in place while holding jurors accountable?

The voir dire (“to speak the truth”) is the process that takes place before a trial when prosecution and defense attorneys are selecting jurors. This is a preliminary exam of potential jurors which elicits information that might shed light on underlying bias or interest in the outcome so that all parties can feel their right to a fair trial is upheld.

At the start of Voir Dire, you go from about 100 jurors to 12, including alternates, in front of the judge with both the prosecution, defense, and defendant present.

Typically, the prosecution gets 8 strikes, and the defense gets 10 strikes. The Voir Dire process can take a single day or even multiple days to accomplish. The strikes are designed to eliminate any jurors that leave either party uneasy at the end of the process.

Honesty is the heart of jury selection. If a juror doesn’t tell the truth, the entire justice system is compromised. When a juror has alternative motives or they lie on their questionnaire, it’s usually grounds for a re-trial.

Sequestering jurors used to be a civilized option designed to protect the basis of our judicial framework, but it's proving absolutely chaotic in 2022. Now, jurors go home to their cell phones and social media outlets that thrive on information overflow which makes exposure to content nearly impossible to ignore or avoid.

The true crime & podcast television genre has become a dominant and profitable market, undoubtedly fueling the uptick of "stealth jurors.” Those who deliberately lie or evade honest disclosure and admissions in order to land themselves a seat on a high-profile jury. Incentives are tainted by the lure of social media fame and profit, knowing they can capitalize on their experience once a trial wraps.

The rise in activism in the last five years has even earned a new catchphrase: “activist juror.” The term is used to describe an individual who takes the opportunity to serve the public by sharing their outspoken nature in interviews, podcasts, and documentaries following their experience. They sell their story to snag a second in the spotlight, but often reveal mishaps and mistakes that would have otherwise gone unchecked.

As Ghislaine Maxwell settles into her new ranks at the Florida prison, her lawyers are hard at work filing her appeal based on Juror '50s misconduct. If you recall, Scotty David lied about a history of sexual abuse on his juror questionnaire and later boasted about how this experience ultimately swayed undecided jurors. One article cited him as claiming to have “helped” other jurors see things from a victim’s point of view. As mentioned above, this would be grounds for immediate retrial, but more and more judges are letting misconduct slip, eroding the integrity of the justice system each time it happens.

In June 2021, Harvey Weinstein was convicted to 23 years in prison by a New York State court, only to win an appeal 13 months later after a juror lied about writing a book about sexual predators.

Enter Trevor Milton. A charismatic billionaire in the tech industry, and early competitor to Elon Musk in the race for zero-emission semi-trucks, is facing up to 20 years or more in prison for defrauding investors by allegedly lying about the company’s progress and Tweeting to inflate the stock price of Nikola.

Milton, the founder of Nikola Motors, first caught my eye in a headline due to an unprecedented bail amount of $100 million dollars. Aside from Rupert Murdoch’s stunning $290 million bond, I couldn’t find anyone else in white-collar crime with a comparable bond.

While researching this staggering bail amount, I came across an interview with jurors from Milton's trial on Inner City Press. The explanation behind their decision to convict Mr. Milton raised red flags after two jurors openly admitted they could not find the intent to harm in any of the counts, which should have warranted an acquittal. After all, criminal intent is what separates a crime from a mistake and is required for a jury to send someone away to prison, lose their liberties, seize assets and rip them away from their families.

I reached out on Twitter to Jenniffer Diroche, Juror #6 on Mr. Milton’s jury. Diroche, a safety director from the Bronx who sat on the 4+ week trial, agreed to an interview.

In our recorded conversation, Diroche walked me through the jury deliberations, admitting yet again that the jury had failed to find any criminal intent inside either of the security fraud counts or the wire fraud counts, but managed to convict Milton anyway.

Shortly after my interview, the confusion over this conviction was raised again in an article in The Wall Street Journal, "Inside a Jury’s Five-Hour Journey to Convict Nikola’s Trevor Milton.”

In this recap, the potential for a faulty conviction appeared to point more at confusing wording on the jury instructions, suggesting that jurors may have “misunderstood the law.”

"The verdict, delivered on Oct. 14, puzzled some court watchers because the two securities-fraud charges involved the same alleged conduct by Mr. Milton and required jurors to make nearly identical findings to convict.” As a matter of law, elements of the crime on count 2 were actually easier to meet than count 1, so it makes no sense why he would have been found guilty on count 1 and not guilty on count 2.

“We thought that he didn’t have an intent to harm,” said Ms. Diroche.

“We think he had good intentions with Nikola,” said Ms. Stringer, juror #1 (jury forewoman.) “It just didn’t come into fruition as quickly as he wanted to. That made him do unsavory things to get it done. But the criminal part of it? We didn’t feel it was anything criminal.”

“If they didn’t find criminal intent, they should have acquitted him for every count,” Mr. Imperatore, a retired attorney added.

Here, in a clip from my interview with Ms. Diroche she explains that there was no intent found for counts 1, 2, 3, or 4 and the jury thought intent was not required to convict Mr. Milton on the other 3 counts.

INTERVIEWER: Just so I get this right, count 1 only needed one of the three requirements to be found guilty and count 2 needed all three requirements to be found guilty. Is that right?

JENNIFFER: That is how we interpreted it, yeah. It was count 2 where we just had an issue.

INTERVIEWER: I am assuming intent was that element missing from.

JENNIFFER: Yeah, intent to harm, yeah

INTERVIEWER: So criminal intent was missing in the 4-week trial?

JENNIFFER: Yeah.

She then goes on further to explain

“INTERVIEWER: So unlike count two, intent was not required to convict in counts 1, 3 or 4?

JENNIFFER: Yeah, because intent was not required on 1,3, or 4.

INTERVIEWER: Okay

JENNIFFER: It was, you know… Did he do it? And we are like ok he did it, yeah

According to juror interviews, the instructions for Mr. Milton’s case were further complicated by the fact the judge put a table of contents at the front of the jury instructions that showed criminal intent was required on count 2 but not counts 1,3 of 4– hence why they found him not guilty on count 2. This was further acknowledged in the WSJ article saying “The first securities count, the three jurors said, was relatively straightforward. They said the jury believed it only needed to find Mr.Milton’s conduct met one of the three criteria in that count, simplifying the discussions.”

It appears the jury misunderstood those instructions on the title page and didn’t read any further into it after that. They convicted him on a subset of an element, rather than a whole count.

Here is further clarification from Juror # 6

JENNIFFER: We read through it and we were like okay so, according to this, he needs to be meeting the criteria.

INTERVIEWER: Okay, so as far as the verdict, from what I have seen online, it seems like a lot of people are confused as to why count 1 was guilty but count 2 was not guilty.

JENNIFFER: Criminal intent is why we found him not guilty on the second count. The first count was like okay did he commit fraud, did he do this, did he do that, but the second one was like, did he intend to harm anyone, and that is where we were split actually, and most of us thought that he didn’t intend to harm anyone.

INTERVIEWER: So I saw Victor in an interview said, if the prosecutors fell short on proving intent to harm during the trial, or actually that was the interviewer, I can’t remember which one it was on, but he asked him if the prosecutors fell short on proving intent to harm during the trial, Victor responded, you nailed it, that was the one area the jury couldn’t find sufficient evidence for. Is that how you would explain it as well?

JENNIFFER: Yeah, yeah that is exactly it.

In other words, the jury didn’t believe that intent was required to find him guilty on the other three counts.

Although it appears Mr. Milton was wrongly convicted, the question is why? Activist Juror, it appears. Regardless of how innocent Milton was according to the law, it appeared someone on that jury had other motives.

Upon closer examination of Ms.Diroche’s social media channels, I spotted several instances where her online footprint showed clear evidence of bias, specifically against wealthy white men. Online, she voiced several criticisms over the gross offset of wealth attached to these types of billionaire success stories.

As for her social media activity, Ms. Diroche appeared to lie on the jury questionnaire.

Voir Dire questions to Juror #6

Jury Questionnaire from Court: What social medial platforms, if any, do you use?

Juror #6: None

After doing some research, it appears Ms. Diroche used Twitter extensively prior to the trial. She tweeted more than 110 tweets, replies, or retweets in the 30 days leading up to the trial and tweeted more than 250 tweets, replies or retweets during the trial.

In our interview she admits to having Twitter and social media since 2008.

“INTERVIEWER: Yeah ok. How long have you had twitter?

JENNIFFER: Um let’s see. I got Twitter in 2008 when it started and then um, like when it was really popular I deleted my account and made a new one recently, I think last year

INTERVIEWER: ok. I noticed one of your Facebook posts um touched on the

JENNIFFER: Twitter

INTERVIEWER: Oh, is it, its maybe it was Twitter,

JENNIFFER: I don’t’ use Facebook

Jury Questionnaire from Court: What publications do you regularly read?

Juror #6: None

Jury Questionnaire from Court: From where do you get your news:

Juror #6: YouTube

Neither of these answers appear truthful. Ms. Diroche in fact follows several new agencies on Twitter with regular updates from their feeds; Washington Post, Associated Press, Reuters, NPR, The New York Times, Time, BBC, Space X, and Elon Musk, among others. She even tweeted some articles from these outlets regarding wealthy people during Mr. Milton’s trial.

This was tweeted during Mr. Milton’s trial. She went on to admit to that in our interview.

INTERVIEWER: So what news outlets do you say you trust the most at this point?

JENNIFFER: Me, I prefer the New York Times, yeah, like if I am going to read something, and the Post, it’s got a little more, and like honestly, the Associated Press, BBC.

Why lie about social media and influential news sources? Because Diroche would have been flagged and struck off the jury, losing any opportunity for an activist platform on social media that is in such high demand right now.

If attorneys had known, for instance, that Diroche intently followed Elon Musk on Twitter, a direct competitor of Nikola Motor Company, she likely would have been dismissed from the jury pool on that alone, considering Elon Musk once called Mr. Milton’s company plan a “Fool Cell,” and Nikola Motor also had a very public multi-billion-dollar lawsuit against Tesla at one point. This is the kind of discovery that would have resulted in an immediate strike if uncovered during the Voir Dire.

Jury Questionnaire from Court: Do you feel that senior-level corporate executives do not deserve or are not worth the money that they earn?

Juror #6: No

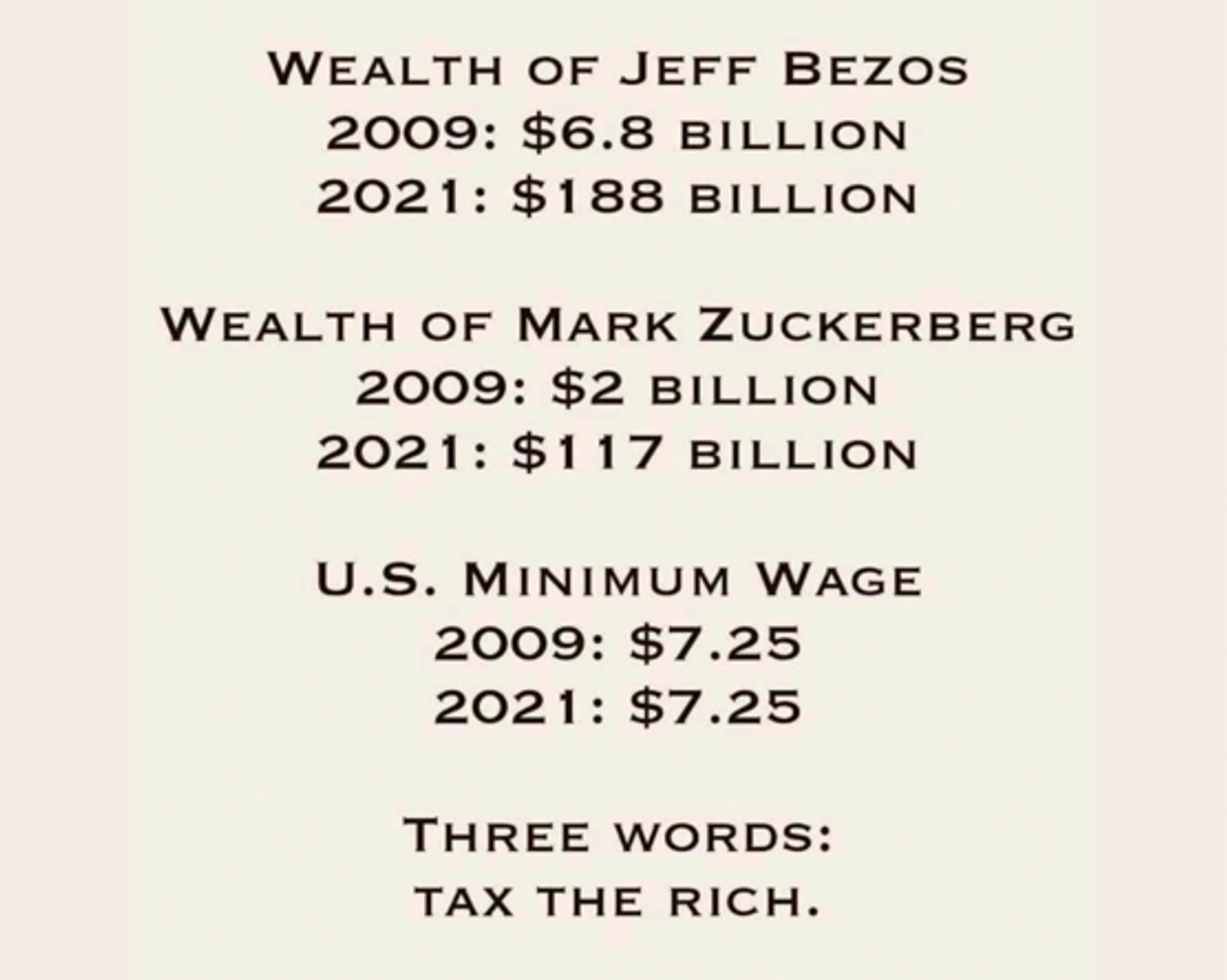

Her answer did not seem right after researching her history on social media. Below, Juror #6 appears to admit that executives do not deserve the money they make.

INTERVIEWER: I had my assistant pull, one of the, well maybe I am hoping this is you, it was talking about the richest men in America, Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg, net worth over 100 billion dollars, and um, like you know, in comparison to the minimum wage which is only $7.25. Do you believe

JENNIFFER: yes

INTERVIEWER: As corporate executives deserve the money they make when the minimum wage is stuck at $7.25 for everyone else?

JENNIFFER: I don’t know where that, maybe that was something I would say, it sounds like something I would say”

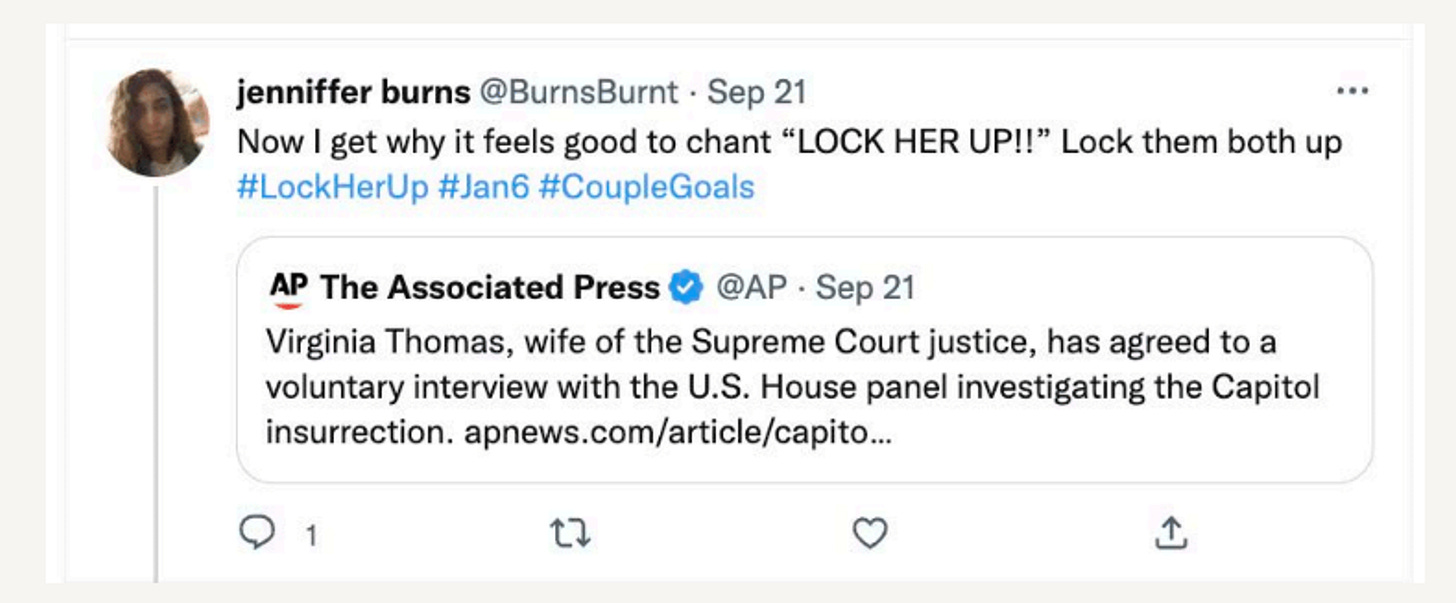

This second Tweet was sent while Juror #6 was sitting on the trial of Mr. Milton.

Here Juror #6 is actively talking about taking money from a wealthy individual and never recovering from it.

She later asks me if Mr. Milton will be required to repay everyone during my interview, which fits this narrative of taking money from or hurting those who are wealthy to a point they can never recover from it.

Juror #6 tweeted at a short seller, post-trial, (Who testified at Mr. Milton’s trial against Mr. Milton) that “you did good man” on getting $600,000 shorting Mr. Milton’s company.

She appears to want Supreme Court Justice Thomas locked up in prison with his wife. This was also tweeted during Mr. Milton’s trial.

Now, here’s the kicker.

In the WSJ interview, Juror #5 admitted that one of the jurors had to go home at 5 PM Friday (The first day of deliberations) and couldn’t come back. She is referring to juror #6.

“The woman said one juror needed to leave at 5 p.m. Ms. Diroche said she couldn’t come back next Monday.”

Another bombshell.

Ms. Gerrity, Juror #5, said “She feared introducing a new juror could have led to a full acquittal of Mr. Milton”

It seems they admitting that if Juror #6 was not able to come back, Mr. Milton might have been acquitted of all charges and found not guilty by another juror.

In this clip, Juror #6 mentions not being able to return for the second day of deliberations. Which she believes might have resulted in a different outcome.

INTERVIEWER: So they gave you an estimate how long the trial would last?

JENNIFFER: Yeah, they have it all timed out.

INTERVIEWER: How did your employer respond to you telling them that you might be on this jury for 5 weeks?

JENNIFFER: I, like, let them know and they just…got back to me a few weeks later after I was already selected like it took a while for them to get back to tell me that I would only be paid for 15 days.

INTERVIEWER: Did you just kind of want to describe what those first moments are like, that first hour in that [jury] room together?

JENNIFFER: Well, we just wanted to get through it mostly cause I know I couldn’t go back, like I said I pay for school out, I am in school, I pay for out of pocket and um, my job wasn’t going to pay me for after 15 days, and I was already losing money being in jury duty

INTERVIEWER: Right

JENNIFFER: So I wasn’t going to be able to go back, like my job was paying me, but I make a lot more money if I have my regular schedule.

INTERVIEWER: Right

JENNIFFER: So the schedule of jury duty is just base salary and that for me, like I need the extra, like I have premiums and I was giving up the premiums for 5 weeks

INTERVIEWER: Wow.

JENNIFFER: Yeah, so that was really, like I was really hurting after a while, like oh my God, I can’t keep doing this.

INTERVIEWER: Yeah.

JENNIFFER: So, then they told me like oh we are not going to pay you anymore, and I’m like ok so I lost my premiums and, um, I'm not going to get paid, im gonna get paid 60, what was it, 40 or 50 bucks for a day? That’s not , that’s not really a lot of money.

INTERVIEWER: Yeah that’s nothing, nothing.

JENNIFFER: And I also didn’t make back like, during the jury duty, we just, I just got the check, I definitely didn’t make back the money I lost so,

INTERVIEWER: right. In what way, if any, would you say this whole experience changed you?

JENNIFFER: eh, I mean I have always been aware of like, hyper-rich people, but I don’t think this, I just feel like bad, that we, like, we didn’t, like maybe I shouldn’t have, uh, like I feel bad because I couldn’t come back that Monday, so maybe I should have just stepped down, just let them keep deliberating, yeah, cause, I mean they had just kept on talking about it, things would have just, there is also the fact that like, we weren’t presented with all the evidence, so he probably would have been found innocent on two, but uh, who knows.”

By the end of this whole examination, it occurred to me what I had (unintentionally) uncovered here.

“Did I just interview a woman who might have wrongly convicted a man based on confusing jury instructions?” I asked a friend, with decent legal knowledge in a text after the WSJ article aired.

“It certainly seems that way.” He wrote back in response.

So there we have it. Evidence that a jury in New York just put a man away for 20 years while openly admitting that he is innocent.

But at least juror #6 made it home by 5 pm.

Activist jurors and activist investors. A whole lot of madness here.

I’m old enough to remember being put on a jury as an honor and privilege. Such a disgrace society can be these days!